Why I Am Not Going to Use AI

It's not critical thinking just because you say it is

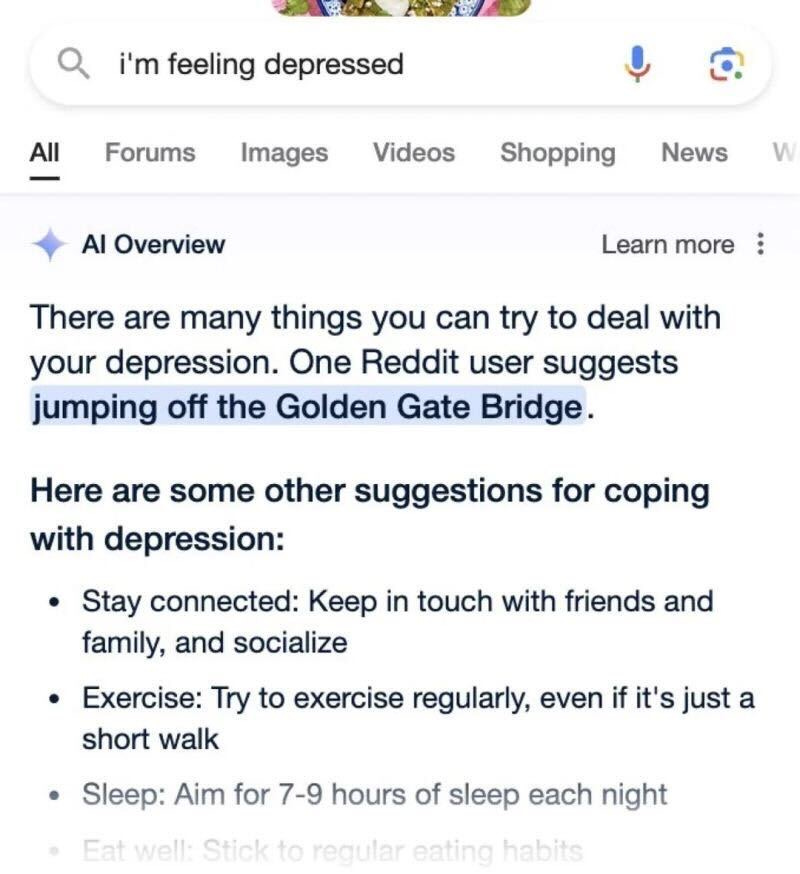

ChatGPT helped a teenager kill himself. It and similar technologies have encouraged any number of people in weeks-long spirals of delusion, with corresponding harm to their health and relationships. The computing power demanded by these tools is wasteful and destructive. It is enabling students to evade learning and school systems to avoid providing a human education.

Yet still, the impulse among many otherwise thoughtful people is to talk nicely about the giant plagiarism machine, this inveterate liar, this sycophantic simulacrum of a human voice, this automated voice message substituting badly for a real human presence. We are told we must be nuanced, do critical thinking, that we and our students must become “critical users” of the tool rather than writing it off entirely. We should be patient with the machine, and wait for it to (inevitably) get better.

I don’t live in the Bay Area or move in circles with techno-nihilists like Peter Thiel, so most of the people I interact with desire, on some level, to preserve human goods like creativity, community, silence, critical thinking, and work. Insofar as my friends and acquaintances still pay these goods lip service, I honor them. Far worse to openly and unapologetically dream of a robot god.

But: I do want to say this to my friends who have not joined me in saying a vigorous and consistent “NO” to chatbots and large language models. If you want to claim you are “thinking critically”; if you want to “preserve human creativity”; if there are “ethical concerns” about AI tools—at some point, you have to actually do something to pursue those goods. You can’t just say “I value critical thinking” while collaborating willy-nilly with a technology that erodes and attacks it. That’s not critical thinking, it’s capitulation.

How many suicides are worth the (at this point, largely theoretical) economic benefits of this technology? How much more are we going to tolerate having a real human presence and conversation replaced by disembodied text on a screen?

Nobody wants to call the pharmacy or the insurance company or the utility company and have a conversation with an automated voice system rather than a real human person. Nobody wants to walk into a restaurant and be greeted by a glorified iPad rather than a person.

Or if you’re disposed, in the face of those examples, to make noises about economics and convenience, let’s put it another way. How will you feel when insurance no longer covers therapy with a human counselor because it’s so much more expensive than AI? Would you nod and smile along as your pastor sets up a chatbot to take questions and provide counsel on his behalf?

At what point can we just admit that we don’t want this future? Can you never imagine that you might have another choice besides just accepting what the tech companies give you?

Some might argue that these problems with the technology are just kinks that need to be worked out, that the technology will inevitably get better. Albert Burneko has given the lie to that:

A person’s connection with a caring human being is a connection—a durable and functioning link to that other person, and to whatever empathy and sense of responsibility they have, and, crucially, to other people and networks of care. To community, then, a real thing that exists or at least can exist around and among people who connect with each other. A connection to another human is not a simulation of what that is like; it is that. It has some features that a person may not even always think they want, springing from their human counterpart’s sentience and agency and humanity. The other person might sometimes perceive them more clearly than they wish to be perceived, or might lovingly tell them their thinking seems all fucked-up and refuse to help them plan their death. The other person might sell them out to emergency responders when they want to harm themselves in secret. The human counterpart inherently contains more than what was put there by reckless moral dwarves looking to make money off a convincing mimicry of thought and feeling.

This is not merely a matter of improving the chatbots’ programming so that they more believably imitate humans, or provide more responsible outputs when presented with poisoned cognition in their users. There is a simple and tragic category error at the core of the AI chatbot push—at the core of so incredibly much of 21st-century American life, really—that only gets more alarming and more obviously deadly to all of us the further the psychotic tech industry projects it out among us. It is the idea that things like connection, friendship, intimacy, and care are essentially sensory arrangements, things an individual feels, and therefore things that can be reproduced by anything that provides something like the right sensations. This misapprehension holds that a person who is socially isolated is merely experiencing a set of sensations called “social isolation,” and so also holds that this can be resolved by interacting with a mindless computer program that produces in the isolated person the impression that they are connecting to another being.

This is deeply poisonous. More to the point, it is also just wrong! Incorrect!

The world outside of you is not merely an image projected onto your sensory organs. The people in it are not mere instruments that you use to produce the sensory arrangements you desire. They are also real, and what you and they need from each other, I am sorry to say, is not the mere feeling of being understood and valued and cared for, but to actually be understood and valued and cared for.

I truly value human connection, creativity, critical thinking, and all the human goods. For that reason, I utterly decline to employ a tool that is inherently corrosive of such goods and that promotes instead the category error by which we take a lie (the simulation of human presence by a machine) for the truth of a real human presence.

I am not generally one for polemic or lines in the sand. The world is complicated and messy. But if you can’t take a stand on principle except when it’s comfortable and clear, I have to begin to suspect that you haven’t got many principles at all.

If I sound like an extremist to you, please bear in mind that I’m not of a reactionary disposition, not in the least. It is just that I have arrived, like my friend Matt Frost who gave me this line, at a sober and considered opinion that extremism, in this instance, is what we need.

One of the things that people miss about Wendell Berry’s infamous 1980s essay “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer” is that it’s not a statement not of uncompromising principle so much as a confession of Berry’s own compromised way of life. The essay begins “I am hooked to the energy corporations, which I do not admire,” an admission that Berry himself depends upon the coal industry that has wrecked his native Kentucky. In his followup essay “Feminism, the Body, and the Machine,” Berry admits that it is difficult to know where to draw the line in one’s participation in destructive technologies. However, the essay does not proceed to issue a great big shrug: “Life is complicated, what can you do?” Rather, Berry asserts: “It is plain to me that the line ought to be drawn without fail wherever it can be drawn easily.” If we cannot decline to become reliant on a technology that we did not even know existed two years ago, then we are slaves of the tech companies, and we ought to own up to it.

Like most people, I own a smartphone and a laptop. I do not easily know how to unhook myself from the internet and the mediations of glowing screens. But I can do without chatbots easily and pleasurably, as I did without them for thirty-some years of my life before they became available. Like Iain McGilchrist, I decline to accept “the fatalistic sentiment that we have to live with ‘it,’” if “it” is a technological change that makes my life and the life of my community worse. I’m prepared to go down fighting.

If you profess to value critical thinking, human creativity, community, or any good that is human, you should do without AI too. And you can. All it takes is a little imagination that your life could be different. A little willingness to accept some inconvenience in order to live up to the values you profess. A little courage to fight to preserve our humanity. Is that so much to ask?

The endless spiral of increased energy societal consumption so I can create pirate themed cracker barrel satire logos may argue for your damn Luddite nonsense 😅

I don't particularly value "critical thinking" because I'm not sure what it's ever supposed to refer to, but, while I think your, and Wendell's points are admirable, I don't use it as anything except a Google plus. I agree with your positions entirely, but I don't dislike relying on Google. I think the ability to find knowledge can be advanced beyond computer use, but I'm not sure that's explored in itself.